Do you create by hand? Do you create with words? Or both?

Yesterday and today, my faculty advisor has observed that although we humans make meaning in verbal and physical ways, for a variety of social reasons authority figures often overcultivate one side or the other. (Or neither, I might add.) Many of us are taught, through schooling, that what we type with our fingers or say with our mouths is more important than what we can make with our hands or sculpt with our bodies.

There’s some overlap here, of course, in that writing (or typing) is an action that lives in our hands. But my advisor’s point is that too often, that’s as far as it goes. Unless we also engage in other activities and ways of thinking (in terms of movement, in terms of texture, in terms of light or temperature or dimension), our writing and meaningmaking will be limited to our hands, rather than involving our entire bodies.

The moment he said this, I got it. When I was younger, before writing took over as the only mode of learning in school (did I create a single physical object in college?), I used to think and create with my hands. I used to make things by hand.

* * * * * *

My mother, being a sentimental soul, and having only one child, has trouble throwing my old things away. The garage of my childhood home is lined with boxes containing elementary school spelling tests, middle-school science papers, and God knows what else. My bedroom, though not exactly as I left it at 17, feels less transformed (say, into a study) than strategically looted, with some walls and drawers empty and others left intact, housing various middle-to-high-school artifacts.

Pretty much every time I visit my parents, I use the desktop computer at least once. And pretty much every time I use the desktop computer, I notice and smile at the following diorama, perched on a nearby shelf in the cluttered study, and crafted by Yours Truly in about the fifth or sixth grade.

Thorin thinks that Bilbo should climb to the top of the tree and see if he can see any end to the forest. Bilbo reluctantly climbs up a tree and breaks through the canopy to the bright light of the sun. He sees thousands of butterflies and looks at “the black emperors for a long time and enjoyed the feel of the breeze in his hair and on his face.” [from The Hobbit, Chapter 8, pg. 148.]

Turns out, I used to love making all kinds of things when I was young. In eighth grade, I was supposed to present a visual aid about immigration to the US at the beginning of the 20th century. I wound up making a simple Rube Goldberg device: on one side of the machine there’s a tiny bucket where you place more and more stick figurines (representing immigrants). When the bucket gets heavy enough, it tips a see-saw that flips a gate, a marble rolls down a pathway and trips something else, and I forget exactly how the rest of it worked but in the end another tiny bucket flips over and out fall all these illustrations of ‘consequences of immigration’ (i.e. tenements, rats, spread of disease, and whatever else our history book told us).

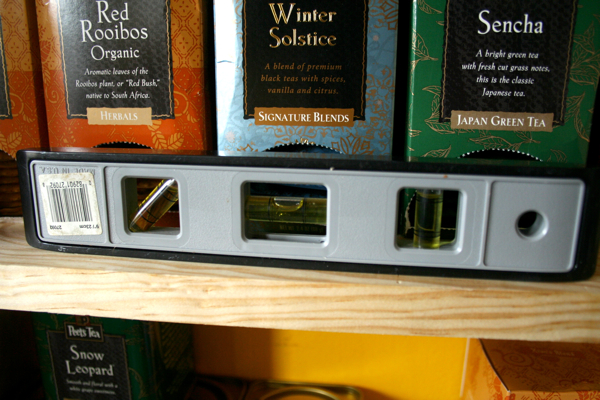

But midway through high school or so, the making of things by hand fell away. It would be years before I rediscovered it: first through cooking, then letter writing, and now bootleg carpentry and picket-sign design. I hesitate to call these activities “making meaning” (sounds so lofty and . . . well . . . discursive), but at least they live in the same neighborhood.

How about you? Do you regularly use your hands to make meaning — playing music, painting, sculpting, deejaying? Or maybe even your entire body, through dance? Or are you mostly brain-mouth-and-keyboard -bound, like me?