Lyrics here.

How many of you have seen Newsies? Easily the best Disney film ever made. Probably the best Disney film even conceivable. (How — how? — did this get greenlighted?) Based on the true events of the 1899 Newsboys’ Strike, it introduces the newsies as a “ragged army” of poor, plucky orphans and runaways who survive by slanging newspapers in the streets of New York. When journalism capitalists Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst collude to expand profits by charging more money to the “distribution apparatus” (a.k.a. these teenage laborers), the newsies, outraged, take inspiration from locally organized trolley workers and decide to go on strike.

They also dance and sing, fabulously.

In a dazzling display of preternaturally sophisticated taste (or as part of a steady diet of musicals my mother supplied me at a young age), I became obsessed with this movie following its release in 1992, when I was six or seven years old. I remember sliding in the VHS (I think my parents had taped it from TV) and sitting on the carpet below the screen, transfixed by Jack Kelley (a young Christian Bale), Spot Collins (the dreamy dangerous one from Brooklyn), and the rest of the balletic, rough-and-tumble weyr. To this day, I can belt out any of its numbers and recite large swaths of dialogue.

But I am hardly alone in this devotion. Recent example: a few weeks ago at an outdoor beer garden, a friend of Ryan’s, visiting from Oregon, joined us in the opening bars of “Seize The Day” so tenderly and sparklingly that we drew astonished compliments from a nearby table. “What was that?” the woman marveled. “It was beautiful!”

Indeed, the enduring cultish popularity of Newsies has now inspired an adaptation for theater. Academy-Award-winning composer Alan Menken is teaming up with Harvey Fierstein to translate the turn-of-the-century David-and-Goliath tale from screen to stage. Unfortunately, however, it appears that the new version is doomed to be bled of much of its political nuance, in favor of (you guessed it) the romance angle. Fierstein explains:

“In a musical, there’s an old rule: You must follow the love story. It gives the audience somewhere to go and someplace to rest their hearts.”

This slated snoozeifying shift is tragic, not because its motivations are wrong, but because they are right. You do need a love story. Thing is, Newsies already has one. But rather than the typical hetero-sapfest, it is chiefly a love story of solidarity: of workers learning to trust, defend, celebrate and enjoy one another.

I’ll admit, at six years old I came at Newsies heart-first. The head came later. But it did come. And this film affords ample room to grow into, intellectually.

So, in honor of one of my favorite movies of all time, here goes a series of posts: on the real-life lessons we can draw from Newsies.

Lesson One: You’ll Have To Deal with the Scabs.

See that song up at the top?

Hear that part (around 0:50) where Boots asks Jack (the leader):

—”What’s to stop someone else from sellin’ our papers?”

—”Well we’ll talk wit’ em.”

—”Some of ’em don’t hear so good.”

—”So we’ll soak ’em!”

“Soaking” is newsie speak for “rolling up on,” or “beating up.” David immediately chimes in with the typical liberal nonviolent objection: No, we can’t be violent! It’ll give us a bad name!

How this violence vs. nonviolence conflict resolves itself through the film testifies to the realism that elevates the movie beyond fun to fascinating. Spoiler: They do use violence. Why? Because they have to, in order to maintain a hard picket line. And this bears out in the history of labor unions in the United States.

In Sylvia Woods’ testimony “You Have To Fight for Freedom,” featured in the collection Rank and File: Personal Histories By Working Class Organizers (edited by Alice and Staughton Lynd), she writes of her upbringing in the 1910’s:

[My father] was a union man. There was a dual union— one for whites and one for blacks. He said we should have one big union but a white and a black is better than none. He was making big money—eight dollars a day. I used to brag that “My father makes eight dollars a day.” But he taught me that “you got to belong to the union, even if it’s a black union. If I wasn’t in the union I wouldn’t make eight dollars a day.”

New Orleans is a trade union town. My father had seen the longshoremen organize and they made a lot of money. Unions were not new to this city. And I mean they had unions! When they came out on strike, there were no scabs. You know why there were no scabs? Because you carried your gun. The pickets had guns and they would blow your brains out.

Real talk. And even though Newsies‘ slightly sanitized brawls depict fists, slingshots, and rotten fruit (the opposing side, with hired Pinkerton types, is armed with much more deadly weapons — chains, bats, and brass knuckles — and backed by police), not to mention the conspicuous absence of racial tensions among the workers, nonetheless, the movie does show them defending their strike from scabs through use of force. Not only shows, but cheers it.

* * *

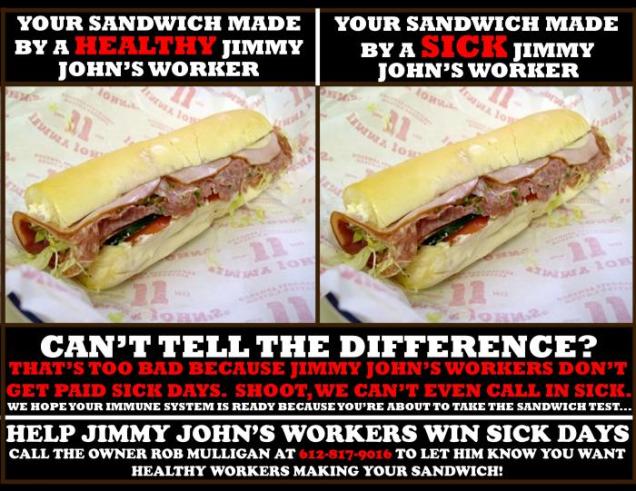

Nowadays, though? Fighting scabs appears to be taboo: at least in mainstream media. Take the recent and relevant example of the ILWU strike up in Washington.

As Darrin Hoop reports for the Socialist Worker:

Longshore workers have shut down ports in the Pacific Northwest as they confront a scab grain terminal operation, block trains, dump grain shipments and stand up to a police attack on their picket lines.

Just two days ago, workers (including the local longshore president) and supporters (mostly women) blocked another train from entering the EGT grain terminal. Police responded with mass arrests and liberal application of pepper spray.

For mounting these defenses, these workers are pilloried as “thugs” and “goons.” A CNN reporters openly laughed at them. Other reporters deny that the ILWU is fighting true scabs at all, claiming that this all boils down to pig-headed union-vs.-union beef. (David Macaray debunks that argument handily.)

Courts, meanwhile, find the ILWU in contempt: which happens in Newsies, too. In fact, one of the film’s greatest political strengths, in my mind, is how it shows the institutional and corporate-backed violence not only matching but outstripping the workers’ use of physical force. Put in this context of severe power imbalance and active repression, the viewer naturally sympathizes with the newsies’ self defense, even if it is technically “criminal.”

But we’ll save the legality subject for the next post in the series.

For now, I am curious, especially from the Buddhist/spiritual folks who live in commitment to nonviolence: how do you propose dealing with scabs? When workers organize to halt production and the company predictably pushes back, what levels of strategic property destruction and physical force, if any, do you find legitimate? Have you ever been in such a situation? (For the record: I haven’t.)

Share your thoughts, and take care. See you next week with more Disney labor lessons!