If you’re looking for an account of the Zen Peacemakers’ Symposium on Western Socially Engaged Buddhism — hosted last month in pastoral Montague, Massachusetts — from a reputable, authoritative, or well-known source, I can tell you right now: you’re barking up the wrong bodhi tree. The Symposium was chock-full of dharma celebrities; I am not among them. I’m not a Roshi, Bhikkhuni, Director, Founder, or Professor. I am a Nobody. At least in this context.

But, you know, a Nobody isn’t such a terrible thing to be. You get a very interesting vantage point as a Nobody. You see things that others don’t get to see.

For example, as a Nobody with No Money, I witnessed the gestation and birth of the volunteer program for the Symposium. Back in January, when I first learned of the national event from an ad in Tricycle magazine, I called up the ZP folks and said, “Hello! I’m interested in socially engaged Buddhism, but I don’t have $600 for registration fees. What can I do?”

Months later, after a few rounds of phone tag (and the beginning of a friendship with fellow young’un and ZP Media Master Ari Pliskin), a Volunteer Application Page was added to the website. Something like 40 people applied to fill 15 slots. And sure enough, the 15 of us who would show up a day early and work the whole week had two things in common.

We were broke, and we were Nobodies.

Except, instead of being Nobodies, we were now Volunteers. A select team.

And we had fun! We stayed in the beautiful ZP farmhouse — beneficiaries of amazing hospitality and generosity from the residents. We joked and collaborated and griped and ate together, bonding over tasks and talks. We even went on group field trips, a couple nights and dawntime mornings. Truly, the Volunteers were a vibrant, splendid bunch, with stellar direction from a pair of unpaid volunteer coordinators, who as far as I’m concerned accomplished the work of five people between the two of them.

And like paying participants, we got to hear and join in the week’s rich conversations, beautifully facilitated and well-crafted (if a little heavy on the lecture-vibe for my tastes). We asked questions, mingled, savored those jolts of mutual recognition with kindred spirits. We also got to discuss with some of our dharma heroes. For me that included Roshi Joan Halifax, Jan Willis, David Loy, Bhikkhu Bodhi, Alan Seunake (who I already knew from the Bay Area), Matthieu Ricard, and Frank Ostaseski.

Still, unlike participants, and unlike presenters, we were Volunteers.

Part of being Volunteers meant a waived registration fee, with all our meals and lodging covered. Everyone felt extremely grateful to the Zen Peacemakers for welcoming us so fully into the household.

But another part of being Volunteers meant taking on responsibilities that prevented us from participating on an equal basis in the week’s events.

Frequently we had to leave presentations early in order to go work a shift.

Occasionally we missed entire morning programs, assembling bag lunches in the caterer’s basement restaurant in nearby Amherst.

Because of a Volunteers meeting, a few of us got pulled out early from the breakout discussion group on Diversity: the sole mini-program, out of a whole 6 days, dedicated to race and all other types of demographic categories. As a Nobody among Nobodies (I may very well have been the only person of color under 30 years old, out of a conference of hundreds), in that moment I felt particularly lonely.

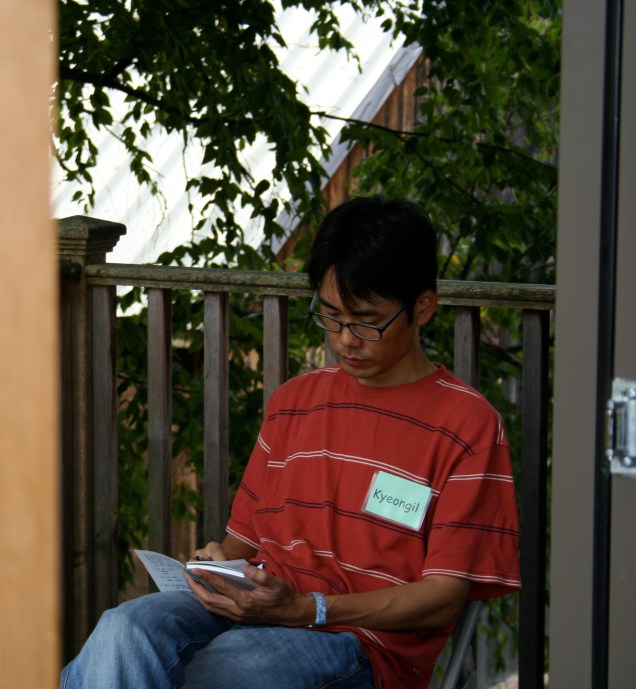

And finally, being a Volunteer meant having a green-colored nametag for the week. Participants had white nametags and presenters had blue ones.

But while everyone else had their first and last names (helpful for recognition and networking purposes), ours had only our first names. Melissa. Karen. Sean. Kyeongil.

(Weeks later, when I told my dad about the Volunteers’ nametags, he said to me, “And I’ll bet you took a marker and wrote in your last name yourself.” Knows me well, that man!)

Now, I really don’t want to paint a negative picture of this tremendous event. And I don’t want to give a false impression: in my human-to-human experiences, no one ever treated me as less-than. On the contrary, it was one of the warmest, most jovial conferences I’ve ever attended. I left feeling inspired to organize a radical sangha in my own community, to collaborate with existing groups in the Bay Area, and to keep up the work of socially engaged dharma with renewed vigor.

But the nametag thing, inconsequential though it might seem, really underscored for me the subtle class hierarchy between workers (Volunteers) and participants. My goodness! If, consciously or unconsciously, we continue to reproduce class divisions and mental/manual labor splits in the name of advancing “Socially Engaged Buddhism,” then it’s almost certainly a doomed movement.

I understand the need to raise funds. I do. But fundraising, while vital to movement building, must never be conflated with it. As much as possible, especially in a Buddhist or dhammic context, we should endeavor to collect what’s needed by promoting dana (generosity), a sense of interdependence, and erosion of the economic and social hierarchies stratifying our society.

Across many different social change movements, this common problem emerges. People with less material wealth automatically wind up washing dishes to ‘earn their place’ in the big annual strategy session. Unfortunately, this is sloppy generosity, and serves no one.

At the same time, washing dishes together can be a great way of strengthening community and camaraderie! Collective manual labor is indispensable to healthy movement activity.

The issue isn’t the volunteer work itself, but whether or not it hinges on obligation — explicit or implicit. There’s a big difference between (1) registering as an event volunteer in order to get in the door, and (2) entering like everyone else, and then signing up, along with anyone else who wishes, to do the work that needs to get done.

Furthermore, the work-exchange problem isn’t only a matter of economics, but diversity, too.

Low-income people, the ones most likely to rely on work-exchanges, are disproportionately young, of-color, queer, criminalized, and marginalized. If we want a diverse movement, we need to make sure everyone enters on as equal a basis as possible.

Many organizations inside and outside of Socially Engaged Buddhism are finding cool, creative ways of solving the money problem for giant gatherings.

Some run almost exclusively on dana (donations), or institute a very manageable sliding-scale fee. Others charge for tickets while encouraging all buyers to purchase an extra for someone who otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford it. Donations (of food, lodging, advertising space) often play a key role.

As Larry Yang of the East Bay Meditation Center says of its dana-based system, the basis is not an economy of exchange. It’s an economy of gift. And what a treasured legacy, passed down through various lineages, spiritual and otherwise.

Would it really be feasible to host an event as large and snazzy as the Symposium using dana or suggested donations alone? Honestly, I don’t know. Maybe we’d need to give up some of the scope and the snazz for the sake of inclusivity and fairness. My hope is that last month’s event will act as a jump-starter for higher sustained levels of regional collaboration among socially engaged and politically active dhamma practitioners.

And maybe the next time we get together on a national level, our enthusiasm, commitment, resourcefulness and generosity will generate a door large enough for everyone to enter as guests; not customers.

In the exquisite Zen Peacemaker spirit of bearing witness, not-knowing, and compassionate action, I believe we can learn from the worldly divides between haves and have-nots, investigate our own blind spots, and skillfully improve on eradicating these hierarchies — the echoes of capitalism — within our own organizations and initiatives. Our means and our ends can better align.

Together, we can move from Nobodies and Somebodies toward Anybody and Everybody.