Today was a great day. In part because I got to learn (and talk to friends) about this teaching model, from the revolutionary Marxist US group Sojourner Truth Organization (STO). So helpful in clarifying some of the qualities I’ve been craving in study groups. More mentorship, active & fruitful diversity of political views. I’m a little skeptical of the way STO seemed to view critique and debate as the only way of co-refining political positions (might write more on that later), but for now, just happily geeking out on the pedagogy.

For Bill Lamme, the appeal as a potential member was the way in which competing views were allowed to contend openly with each other inside the group:

I was particularly attracted to the fact that there was a significant number of very strong intellects with good positions in the group. It was not a single-leader type group, you know, where everybody else is kind of carrying out the [orders] from a very narrow central committee. Debate was so wide ranging, and I had had enough exposure to that early on, that I thought, this is cool. This is cool, because I don’t have to say anything I don’t think, you know, I’m not obligated to mouth somebody else’s position. And what’s more, some of these people are quite brilliant, and I can probably learn a lot in this group. And the fact that there’s more than one brilliant person, that means I’m not just going to eat what one person is shooting out there because there’s nothing else. In fact, there’s a lot of ideas contending. I think that is part of STO’s greatness, as great as it ever was: the fact that it had some really outstanding revolutionary thinkers who were able to butt heads in a very constructive way.

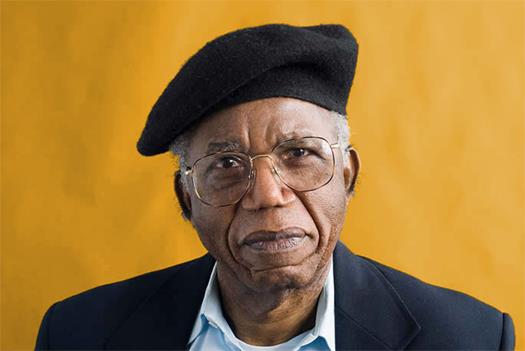

…Still, the situation was never perfect. Many members had long complained about the dominating presence of a handful of intellectual ‘heavies’ who frequently monopolized political debate, whether intentionally or not. Hamerquist, Ignatin, and (after he joined the group in 1976) Lawrence were most frequently identified in this category, and all three of them were well aware of the problem. By the mid-seventies, they and the rest of the organization determined that something needed to be done. While STO, like most other left groups of the era, had long prioritized collective study of key political texts, the group took this emphasis to a new level. Around 1977, Ken Lawrence was initially assigned the task of developing an intensive political education course on dialectics. The explicit goal was to avoid approaching students as empty vessels waiting to be filled with knowledge. At the same time, there was no pretence that all participants had the same level of understanding. Instead, the idea was to train STO members, especially newer ones, in the methods of critical thinking that were essential to the work of theorizing and implementing revolutionary politics.

Taking its cue from the Bolshevik study of Hegel and dialectics, the curriculum began by quoting Lenin’s observation that “People for the most part (99 percent of the bourgeoisie, 98 percent of the liquidators, about 60–70 percent of the Bolsheviks) don’t know how to think, they only learn the words by heart.” Of course there were clear limits on what could be accomplished in a single course of study, but the immediate objective for students was to gain a “functional ability to use Marxism. This is quite different from the usual introductory course which intends to convince the newcomer of the value of Marxism and to familiarize her/him with its terms and scope, but on the whole to leave the important decisions to the more advanced.” Toward this end, participants in the course were encouraged to continue their study, both individually and collectively, and to judge their own progress in the realm of social struggle rather than abstract knowledge. The dialectics course was intended to be “armament, preparation for battle. The test of that will be in our political practice.”

Part of what made the dialectics course unique was its combination of length and intensity. By the time the curriculum was published in Urgent Tasks in 1980, it contained nine distinct parts, which were generally taught more or less continuously over a fairly short time-frame. Hal Adams recalled years afterward that “people had to go for a week, five days or seven days or something, and it was all day long. Other people had to cover for your political work, you had to take your vacation time to go, and it would be in some rural setting. The materials were distributed ahead of time, and you were expected to read them. There were study questions and you would go over them.” The sections covered topics like “Base and Superstructure In Motion,” “How Revolutionaries Are Made,” and “The Marxist Method.” Extensive readings from Marx, Engels, and Lenin were interspersed with selections from a wide range of other thinkers and writers, both historical and contemporary: Hegel, Luxemburg, Gramsci, Lukacs, Mark Twain, CLR James, WEB DuBois, George Rawick, among many others. STO itself was represented by short pieces from both Ken Lawrence and Noel Ignatin. A standard course had perhaps a dozen total participants, with roughly four “teachers” and eight “students.” This allowed for both the competing views among instructors that Bill Lamme appreciated and for individualized attention for each new participant. While the eventual goal was to level the intellectual playing field inside STO, the dialectics course deliberately reflected the reality of uneven development within the group. According to Adams, for each session,

there would be one of the leaders who would be in charge of organizing the discussion, and people were encouraged to talk. They made a big thing that it wasn’t just a circle discussion, because a lot of what was going on in the left at that point was open circle discussion and no matter what anybody said, it was accepted as equal. And this wasn’t that, because there was stuff that was hard to understand… So that there was a role for a teacher to play in the thing.

…

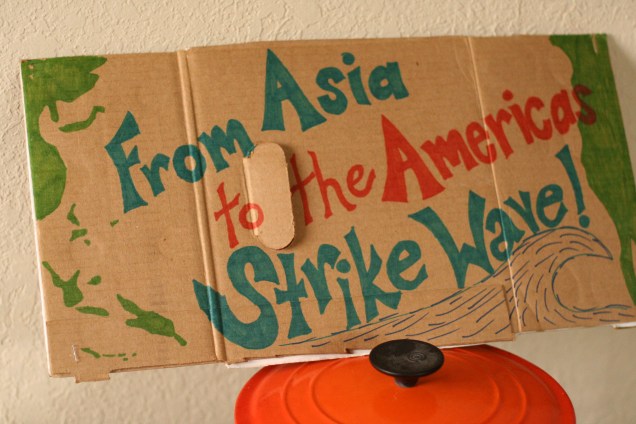

In the end, STO’s dialectics courses took on a modest life of their own, and managed to far outlast the organization that initiated them; in the last decade, several versions of the course have been offered in multiple cities across the US, with the help of a handful of former STO members. Certainly the course changed the self-understanding of many of the participants. Former member Carol Hayse credits Lawrence in particular with having insisted that he could “make theoreticians out of all of you.” Although she initially refused to believe it was possible, she acknowledges that, in fact, “that son-of-a-bitch made a theoretician out of me!” And she was certainly not the only one.